Jacques de Molay

| Jacques de Molay | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | c. 1240–1250[1] |

| Died | March 1314 Paris, France |

| Nationality | Burgundian |

| Known for | Grand Master of the Knights Templar |

- This article is about the Templar Grand Master. For the Mongol general, see Mulay.

James of Molay (French: Jacques de Molay) (c. 1240/1250 – March 1314[1]) was the 23rd and last Grand Master of the Knights Templar, leading the Order from April 20, 1292 until the Order was dissolved by order of Pope Clement V in 1312.[2] Though little is known of his actual life and deeds except for his last years as Grand Master, he is the best known Templar, along with the Order's founder and first Grand Master, Hugues de Payens (1070–1136). Jacques de Molay's goal as Grand Master was to reform the Order, and adjust it to the situation in the Holy Land during the waning days of the Crusades. As European support for the Crusades had dwindled, other forces were at work which sought to disband the Order and claim the wealth of the Templars as their own. King Philip IV of France, deeply in debt to the Templars, had Molay and many other French Templars arrested in 1307 and tortured into making false confessions. When Molay later retracted his confession, Philip had him burned at the stake on an island in the Seine river in Paris, on March 1314. The sudden end of both the centuries-old order of Templars, and the dramatic execution of its last leader, turned Jacques de Molay into a legendary figure. The fraternal order of Freemasonry has also drawn upon the Templar mystique for its own rituals and lore, and today there are many modern organizations which draw their inspiration from the memory of Jacques de Molay.

Contents |

Youth

Little is known of his early years, but Jacques de Molay was probably born in Molay, Haute-Saône in the county of Burgundy, at the time a territory ruled by Otto III as part of the Holy Roman Empire, and in modern times in the area of Franche-Comté, northeastern France. His birth year is not certain, but judging by statements made during the later trials, was probably between 1240 and 1250. He was born as most Templar knights were, into a family of minor or middle nobility.[1] It is said he was dubbed a Knight at age 21 in 1265 and that he was executed in 1314 at age 70. These two facts lead to the belief that he was born in 1244.

In 1265, as a young man, he was received into the Order of the Templars in a chapel at the Beaune House, by Humbert de Pairaud, the Visitor of France and England. Another prominent Templar in attendance was Amaury de la Roche, Templar Master of the province of France.[2][3]

Around 1270, Molay went to the East (Outremer), though little is remembered of his activities for the next 20 years.[3]

Grand Master

After the Fall of Acre to the Egyptian Mamluks in 1291, the Franks (Europeans) who were able to do so retreated to the island of Cyprus. It became the headquarters of the dwindling Kingdom of Jerusalem, and the base of operations for any future military attempts by the Crusaders against the Egyptian Mamluks, who for their part were systematically conquering any last Crusader strongholds on the mainland. Templars in Cyprus included Jacques de Molay and Thibaud Gaudin, the 22nd Grand Master. During a meeting assembled on the island in the autumn of 1291, Jacques de Molay spoke of reforming the Order, and put himself forward as an alternative to the current Grand Master. Gaudin died around 1292, and as there were no other serious contenders for the role at the time, Molay was soon elected. In spring 1293, he began a tour of the West to try to muster more support for a reconquest of the Holy Land. Developing relationships with European leaders such as Pope Boniface VIII, Edward I of England, James I of Aragon and Charles II of Naples, Molay's immediate goals were to strengthen the defence of Cyprus, and rebuild the Templar forces.[4] From his travels, he was able to secure authorization from some monarchs for the export of supplies to Cyprus, but could obtain no firm commitment for a new Crusade.[5] There was talk of merging the Templars with one of the other military orders, the Knights Hospitaller. The Grand Masters of both orders opposed such a merger, but pressure increased from the Papacy.

It is known that Molay held two general meetings of his order in southern France, at Montpellier in 1293 and at Arles in 1296, where he tried to make reforms. In the autumn of 1296 Molay was back in Cyprus to defend his order against the interests of Henry II of Cyprus, which conflict had its roots back in the days of Guillaume de Beaujeu.

From 1299 to 1303, Jacques de Molay was engaged in planning and executing a new attack against the Mamluks. The plan was to coordinate actions between the Christian military orders, the King of Cyprus, the aristocracy of Cyprus, the forces of Cilician Armenia, and a new potential ally, the Mongols of the Ilkhanate (Persia), to oppose the Egyptian Mamluks and retake the coastal city of Tortosa in Syria.

For generations, there had been communications between the Mongols and Europeans towards the possibility of forging a Franco-Mongol alliance against the Mamluks, but without success. The Mongols had been repeatedly attempting to conquer Syria themselves, each time being forced back either by the Egyptian Mamluks, or having to retreat because of a civil war within the Mongol Empire, such as having to defend from attacks from the Mongol Golden Horde to the north. In 1299, the Ilkhanate again attempted to conquer Syria, having some preliminary success against the Mamluks in the Battle of Wadi al-Khazandar in December 1299. In 1300, Jacques de Molay and other forces from Cyprus put together a small fleet of 16 ships which committed raids along the Egyptian and Syrian coasts. The force was commanded by King Henry II of Jerusalem, the king of Cyprus, accompanied by his brother, Amalric, Lord of Tyre, and the heads of the military orders, with the ambassador of the Mongol leader Ghazan also in attendance. The ships left Famagusta on July 20, 1300, and under the leadership of Admiral Baudouin de Picquigny, raided the coasts of Egypt and Syria: Rosette,[6] Alexandria, Acre, Tortosa, and Maraclea, before returning to Cyprus.[7]

The Cypriots then prepared for an attack on Tortosa in late 1300, sending a joint force to a staging area on the island of Ruad, from which raids were launched on the mainland. The intent was to establish a Templar bridgehead to await assistance from Ghazan's Mongols, but the Mongols failed to appear in 1300. The same happened in 1301 and 1302, and the island was finally lost in the Siege of Ruad on September 26, 1302, eliminating the Crusaders' last foothold near the mainland.

Following the loss of Ruad, Molay abandoned the tactic of small advance forces, and instead put his energies into trying to raise support for a new major Crusade, as well as strengthening Templar authority in Cyprus. When a power struggle erupted between King Henry II and his brother Amalric, the Templars supported Amalric, who took the crown and had his brother exiled in 1306. Meanwhile, pressure increased in Europe that the Templars should be merged with the other military orders, perhaps all placed under the authority of one king, and that individual should become the new King of Jerusalem when it was conquered.[8]

Travel to France

In 1305, the newly elected Pope Clement V asked the leaders of the military orders for their opinions concerning a new crusade and the merging of the orders. Jacques de Molay was asked to write memoranda on each of the issues, which he did during the summer of 1306.[9] Molay was opposed to the merger, believing instead that having separate military orders was a stronger position, as the missions of each order were somewhat different. He was also of the belief that if there were to be a new crusade, it needed to be a large one, as the smaller attempts were not effective.[8][10]

On June 6, the leaders of both the Templars and the Hospitallers were officially asked to come to the Papal offices in Poitiers to discuss these matters, with the date of the meeting scheduled as All Saints Day in 1306, though it later had to be postponed due to the Pope's illness with gastro-enteritis. Molay left Cyprus on 15 October, arriving in France in late 1306 or early 1307; however, the meeting was again delayed until late May due to the Pope's illness.[10]

King Philip IV of France was at war with the English, and deeply in debt to the Templars. He was in favor of merging the Orders under his own command, to make himself Rex Bellator or War King, but Molay rejected this idea. Philip was already at odds with the papacy, trying to tax the clergy, and had been attempting to assert his own authority as higher than that of the Pope. For this, one of Clement's predecessors, Pope Boniface VIII, had attempted to have Philip excommunicated, but Philip then had Boniface abducted and charged with heresy. The elderly Boniface was rescued, but then died of shock shortly thereafter. His successor Pope Benedict VIII did not last long, dying in less than a year,[11] possibly poisoned via Philip's councillor Guillaume de Nogaret. It took a year to choose the next Pope, the Frenchman Clement V, who was also under strong pressure to bend to Philip's will. Clement moved the Papacy from Italy to Poitiers, France, where Philip continued to assert more dominance over the Papacy and the Templars.

The leader of the Hospitallers, Fulk de Villaret was also delayed in his travel to France, as he was engaged with a battle at Rhodes. He did not arrive until late Summer,[10] so while waiting for his arrival, Molay met with the Pope on other matters, one of which was the charges by one or more ousted Templars who had made accusations of impropriety in the Templars' initiation ceremony. Molay had already spoken with the king in Paris on June 24, 1307 about the accusations against his order and was partially reassured. Returning to Poitiers, Molay asked the pope to set up an inquiry to quickly clear the Order of the rumours and accusations surrounding it, and the pope convened an inquiry on 24 August.

Arrest

On September 14, Philip took advantage of the rumors and inquiry to begin his move against the Templars, sending out a secret order to his agents in all parts of France to implement a mass arrest of all Templars at dawn on October 13. Philip wanted the Templars arrested, and their possessions confiscated, to incorporate their wealth into the Royal Treasury. Jacques de Molay was in Paris on October 12, where he was a pallbearer at the funeral of Catherine of Courtenay, wife of Count Charles of Valois, and sister-in-law of King Philip. In a dawn raid on Friday, October 13, 1307, Jacques de Molay and sixty of his Templar brothers were arrested. Philip then had the Templars charged with heresy and many other trumped-up charges, most of which were identical to the charges which had previously been leveled by Philip's agents against Pope Boniface VIII.

During forced interrogation by royal agents at the University of Paris on October 24/25, Molay confessed that the Templar initiation ritual included "denying Christ and trampling on the Cross". He was also forced to write a letter asking every Templar to admit to these acts. Under pressure from Philip IV, Pope Clement V ordered the arrest of all the Templars throughout Christendom.

The pope still wanted to hear Jacques de Molay's side of the story, and dispatched two cardinals to Paris in December 1307. In front of the cardinals, Molay retracted his earlier confessions. A power struggle ensued between the king and the pope, which was settled in August 1308 when they agreed to split the convictions. Through the papal bull Faciens misericordiam the procedure to prosecute the Templars was set out on a duality where one commission would judge individuals of the Order and a different commission would judge the Order as an entity. Pope Clement called for an ecumenical council to meet in Vienne in 1310 to decide the future of the Templars. In the meantime, the Order's dignitaries, among them Jacques de Molay, were to be judged by the pope.

In the royal palace at Chinon, Jacques de Molay was again questioned by the cardinals, but this time with royal agents present, and he returned to his forced admissions made in 1307. In November 1309, the Papal Commission for the Kingdom of France began its own hearings, during which Molay again recanted, stating that he did not acknowledge the accusations brought against his order.

Any further opposition by the Templars was effectively broken when Philip used the previously forced confessions to sentence 54 Templars to be burnt at the stake on May 10–12, 1310.

The council which had been called for 1310 was delayed for two years due to the length of the trials, but finally was convened in 1312. On March 22, 1312, at the Council of Vienne, the Order of the Knights Templar was abolished by papal decree.

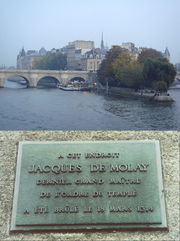

Molay's sentencing took another two years. On March 10, 1314, three cardinals sent by the pope sentenced Molay and three other Templar dignitaries, Hugues de Pairaud, Geoffroi de Charney and Geoffroy de Gonneville, to life imprisonment. Pairaud and Gonneville accepted their fate, but the 70-year-old Jacques de Molay rose up and again recanted publicly. His associate Geoffroi de Charney rallied to his side, and both loudly proclaimed the innocence of themselves and their Order. Philip's response was to order both to be executed immediately as relapsed heretics. that very night, Jacques de Molay and Geoffroy de Charney were taken to the Isle des Juifs, now incorporated into the Île de la Cité in the Seine River in the center of Paris, where they were burned at the stake. According to legend, Jacques de Molay asked for his hands to be left free so that he could keep them together in prayer, while facing the nearby Notre Dame Cathedral. Another oft-told tale is that he called out from the flames that both Philip and Clement would soon meet him before God. Clement did indeed die of illness just a few months later, and a few months after that, Philip was killed in a hunting accident.

Death

Of his death it is recorded: (The account varies by one day, not unusual for chronicles of the middle ages), "The cardinals dallied with their duty until March 19, 1314, when, on a scaffold in front of Notre Dame, Jacques de Molay, Templar Grand Master, Geoffroi de Charney, Master of Normandy, Ilugues de Peraud, Visitor of France, and Godefroi de Gonneville, Master of Aquitaine, were brought forth from the jail in which for nearly seven years they had lain, to receive the sentence agreed upon by the cardinals, in conjunction with the Archbishop of Sens and some other prelates whom they had called in. Considering the offences which the culprits had confessed and confirmed, the penance imposed was in accordance with rule—that of perpetual imprisonment. The affair was supposed to be concluded when, to the dismay of the prelates and wonderment of the assembled crowd, de Molay and Geoffroi de Charney arose. They had been guilty, they said, not of the crimes imputed to them, but of basely betraying their Order to save their own lives. It was pure and holy; the charges were fictitious and the confessions false. Hastily the cardinals delivered them to the Prevot of Paris, and retired to deliberate on this unexpected contingency, but they were saved all trouble. 'When the news was carried to Philippe he was furious. A short consultation with his council only was required. The canons pronounced that a relapsed heretic was to be burned without a hearing; the facts were notorious and no formal judgment by the papal commission need be waited for. That same day, by sunset, a pile was erected on a small island in the Seine, the Isle des Juifs, near the palace garden. There de Molay and de Charney were slowly burned to death, refusing all offers of pardon for retraction, and bearing their torment with a composure which won for them the reputation of martyrs among the people, who reverently collected their ashes as relics."[12]

Chinon Parchment

In 2002, Dr. Barbara Frale found a copy of the Chinon Parchment in the Vatican Secret Archives, a document which explicitly confirms that in 1308 Pope Clement V absolved Jacques de Molay and other leaders of the Order including Geoffroi de Charney and Hugues de Pairaud. She published her findings in the Journal of Medieval History in 2004.[13]

Legends

The sudden arrest of the Templars, the conflicting stories about confessions, and the dramatic deaths by burning, generated many stories and legends about both the Order, and its last Grand Master.

Conquest of Jerusalem

In France in the 19th century, false stories circulated that Jacques de Molay had captured Jerusalem in 1300. These rumors are likely related to the fact that the medieval historian the Templar of Tyre wrote about a Mongol general named "Mulay" who occupied Syria and Palestine for a few months in early 1300.[14] The Mongol Mulay and the Templar Jacques de Molay were entirely different people, but some historians regularly confused the two.

The confusion was enhanced in 1805, when the French playwright/historian François Raynouard made claims that Jerusalem had been captured by the Mongols, with Jacques de Molay in charge of one of the Mongol divisions.[14] "In 1299, the Grand-Master was with his knights at the taking of Jerusalem."[15] This story of wishful thinking was so popular in France, that in 1846 a large-scale painting was created by Claude Jacquand, entitled Molay Prend Jerusalem, 1299 ("Molay Takes Jerusalem, 1299"), which depicts the supposed event. Today the painting hangs in the Hall of the Crusades in the French national museum in Versailles.[16]

In the 1861 edition of the French encyclopedia, the Nouvelle Biographie Universelle, it even lists Jacques de Molay as a Mongol commander in its "Molay" article:

"Jacques de Molay was not inactive in this decision of the Great Khan. This is proven by the fact that Molay was in command of one of the wings of the Mongol army. With the troops under his control, he invaded Syria, participated in the first battle in which the Sultan was vanquished, pursued the routed Malik Nasir as far as the desert of Egypt: then, under the guidance of Kutluk, a Mongol general, he was able to take Jerusalem, among other cities, over the Muslims, and the Mongols entered to celebrate Easter"—Nouvelle Biographie Universelle, "Molay" article, 1861.[14]

Modern historians, however, state that the truth of the matter is this: There are indeed numerous ancient records of Mongol raids and occupations of Jerusalem (from either Western, Armenian or Arab sources), and in 1300 the Mongols did achieve a brief victory in Syria which caused a Muslim retreat, and allowed the Mongols to launch raids into the Levant as far as Gaza for a period of a few months. During that year, rumors flew through Europe that the Mongols had recaptured Jerusalem and were going to return the city to the Europeans. However, this was only an urban legend, as the only activities that the Mongols had even engaged in were some minor raids through Palestine, which may or may not have even passed through Jerusalem itself.[3][17] And regardless of what the Mongols may or may not have done, Jacques de Molay was never a Mongol commander, and probably never set foot in Jerusalem.

The Shroud of Turin

Freemasons often weave legends around the life and legacy of Jacques de Molay, claiming with little or no proof that Molay was a key figure connected to other stories of mystery. In the 2001 book The Second Messiah: Templars, the Turin Shroud, and the Great Secret of Freemasonry, is a claim that the Turin Shroud is actually an image of Jacques de Molay, not of Jesus Christ as is common belief.

There is no reliable basis for saying that the Shroud depicts Molay; however, it is true that there seems to be a connection between the provenance of the Shroud of Turin and the Templars. The French Knight Geoffroi de Charny's widow, Jeanne de Vergy, is the first reliably recorded owner of the Turin shroud. Some believe that her husband of similar name was nephew to Geoffroi de Charney Geoffroi de Charney, Preceptor of Normandy for the Knights Templar, and the associate of Jacques de Molay who was both sentenced to lifetime imprisonment with him, and then burned at the stake with him in 1314 after both proclaimed their innocence.

Curse

It is said that Jacques de Molay cursed King Philip IV of France and his descendants from his execution pyre. The story of the shouted curse appears to be a combination of words by a different Templar, and those of Jacques de Molay. An eyewitness to the execution stated that Molay showed no sign of fear, and told those present that God would avenge their deaths.[18] Another variation on this story was told by the contemporary chronicler Ferretto of Vicenza, who applied the idea to a Neapolitan Templar brought before Clement V, whom he denounced for his injustice. Some time later, as he was about to be executed, he appealed 'from this your heinous judgement to the living and true God, who is in Heaven', warning the pope that, within a year and a day, he and Philip IV would be obliged to answer for their crimes in God's presence.[19]

It is true that Philip and Clement V both died within a year of Molay's execution, Clement finally succumbing to a long illness on April 20, 1314 and Philip in a hunting accident. Then followed the rapid succession of the last Direct Capetian kings of France between 1314 and 1328, the three sons of Philip IV. Within 14 years from the death of Jacques de Molay, the 300-year-old House of Capet collapsed. This series of events forms the basis of Les Rois Maudits (The Accursed Kings), a series of historical novels written by Maurice Druon between 1955 and 1977, which was also turned into two French television miniseries in 1972 and 2005.

In Germany, Philip's "death was spoken of as a retribution for his destruction of the Templars, and Clement was described as shedding tears of remorse on his death-bed for three great crimes, the poisoning of Henry VI, and the ruin of the Templars and Beguines."[20]

Freemasonry

400 years after the death of Jacques de Molay and the dissolution of the Knights Templar, the fraternal order of Freemasonry began to emerge in northern Europe. The Masons developed an elaborate mythos about their Order, and some claimed heritage from entities in history,[21] ranging from the mystique of the Templars to the builders of Solomon's Temple and the pyramids. The story of Jacques de Molay's brave defiance of his inquisitors, has been incorporated in various forms into Masonic lore. Some modern youth groups in Freemasonry are even named after the Grand Master, such as DeMolay International. The stories of the Templars' secret initiation ceremonies also proved a tempting source for Masonic writers who were creating new works of pseudohistory. As described by modern historian Malcolm Barber in The New Knighthood: "It was during the 1760s that German masons introduced a specific Templar connection, claiming that the Order, through its occupation of the Temple of Solomon, had been the repository of secret wisdom and magical powers, which James of Molay had handed down to his successor before his execution and of which the eighteenth-century freemasons were the direct heirs."[22]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Demurger, pp. 1-4. "So no conclusive decision can be reached, and we must stay in the realm of approximations, confining ourselves to placing Molay's date of birth somewhere around 1244/5 – 1248/9, even perhaps 1240–1250."

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Jacques de Molai", Catholic Encyclopedia

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Demurger, Last Templar

- ↑ Martin, p. 113

- ↑ Nicholson, p. 200

- ↑ Demurger, p. 147

- ↑ Schein, 1979, p. 811

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Nicholson, p. 204

- ↑ Read, The Templars, p. 262

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Martin, pp. 114–115

- ↑ Nicholson, p. 201

- ↑ A History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages Vol. III by Henry Charles Lea, NY: Hamper & Bros, Franklin Sq. 1888 p.325. Not in copyright.

- ↑ Frale, Barbara (2004). "The Chinon chart - Papal absolution to the last Templar, Master Jacques de Molay". Journal of Medieval History 30 (2): 109–134. doi:10.1016/j.jmedhist.2004.03.004. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VC1-4CC314K-3&_user=1589142&_handle=V-WA-A-W-Z-MsSAYWW-UUA-U-AAVADBEZEV-AABEBWUVEV-ZBZVECBYZ-Z-U&_fmt=summary&_coverDate=06%2F30%2F2004&_rdoc=2&_orig=browse&_srch=%23toc%235941%232004%23999699997%23504102!&_cdi=5941&view=c&_acct=C000053912&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=1589142&md5=cc8dc869d6bc4326929c25a42c118a60.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Demurger, pp. 203–204

- ↑ "Le grand-maître s'etait trouvé avec ses chevaliers en 1299 à la reprise de Jerusalem." François Raynouard (1805). "Précis sur les Templiers". http://www.mediterranees.net/moyen_age/templiers/raynouard/precis.html.

- ↑ Claudius Jacquand (1846). "Jacques Molay Prend Jerusalem.1299" (painting). Hall of Crusades, Versailles. http://www.culture.gouv.fr/public/mistral/joconde_fr?ACTION=RETROUVER&FIELD_98=REPR&VALUE_98=Molay%20Jacques&NUMBER=2&GRP=0&REQ=%28%28Molay%20Jacques%29%20%3aREPR%20%29&USRNAME=nobody&USRPWD=4%24%2534P&SPEC=1&SYN=1&IMLY=&MAX1=1&MAX2=250&MAX3=250&DOM=All. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ↑ Schein, "Gesta Dei per Mongolos"

- ↑ Barber, The Trial of the Templars, 2nd ed. p. 357 "The account given by the continuator of William Nangis is confirmed by the clerk, Geoffrey of Paris, apparently an eyewitness, who describes Molay as showing no sign of fear and, significantly, as telling those present that God would avenge their deaths."

- ↑ Ferretto of Vicenza, 'Historia rerum in Italia gestarum ab anno 1250 as annum usque 1318', c. 1328) in Malcolm Barber's, The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple (Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 314–315.

- ↑ A History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages Vol. III by Henry Charles Lea, NY: Hamper & Bros, Franklin Sq. 1888 p.326 Not in copyright.

- ↑ Martin, p. 142

- ↑ Barber, The New Knighthood, pp. 317–318

Sources

- Barber, Malcolm (1994). The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521420415.

- Barber, Malcolm (2001). The Trial of the Templars (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-67236-8.

- "Jacques de Molay". The Catholic Encyclopedia. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10433a.htm. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- Demurger, Alain (2004). The Last Templar - The Tragedy of Jacques de Molay, Last Grand Master of the Temple (Translated into English by Antonia Nevill), Profile Books LTD, ISBN 1-86197-529-5 (First publication in France in 2002 as Jacques de Molay: le crépuscule des templiers by Éditions Payot & Rivages).

- Frale, Barbara (2009), The Templars - The secret history revealed, Maverick House Publishers, ISBN 978-1-905379-60-6.

- Lea, Henry Charles (1887). "Chapter V.—Political Heresy Utilized by the State". A History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages. III. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 238–333. http://books.google.com/books?id=DU4-AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA238#v=onepage&q=&f=false. Retrieved 2010-03-30.

- Martin, Sean (2005). The Knights Templar: The History & Myths of the Legendary Military Order. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 1560256451.

- Nicholson, Helen (2001). The Knights Templar: A New History. Stroud: Sutton. ISBN 0750925175.

- Read, Piers (2001). The Templars. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306810719.

- Schein, Sylvia (October 1979). "Gesta Dei per Mongolos 1300. The Genesis of a Non-Event". The English Historical Review 94 (373): 805–819. doi:10.1093/ehr/XCIV.CCCLXXIII.805. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0013-8266(197910)94:373%3C805:GDPM1T%3E2.0.CO;2-8.

Further reading

- Archivio Segreto Vaticano (2007), Processus Contra Templarios (Prosecution Against the Templars), ISBN 978-8-885042-52-0.

External links

- "Jacques de Molay's Site of Execution". crusader.org. http://www.crusader.org.uk/jdm/index.html. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- Jacques de Molay in Medieval History of Navarre

| Preceded by Thibaud Gaudin |

Grand Master of the Knights Templar 1292–1314 |

Succeeded by Order abolished |